Jim Sanborn

(American, b. 1945)

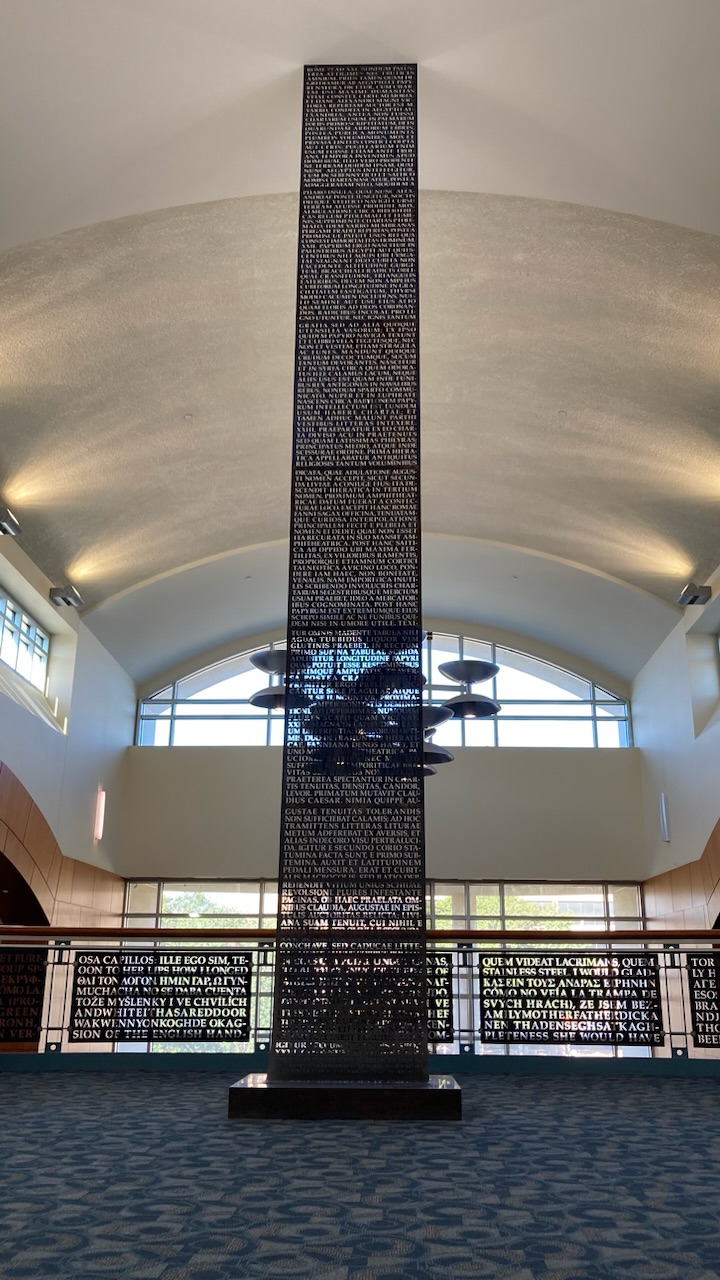

Pliny’s Papyrus, 2003

Bronze and copper

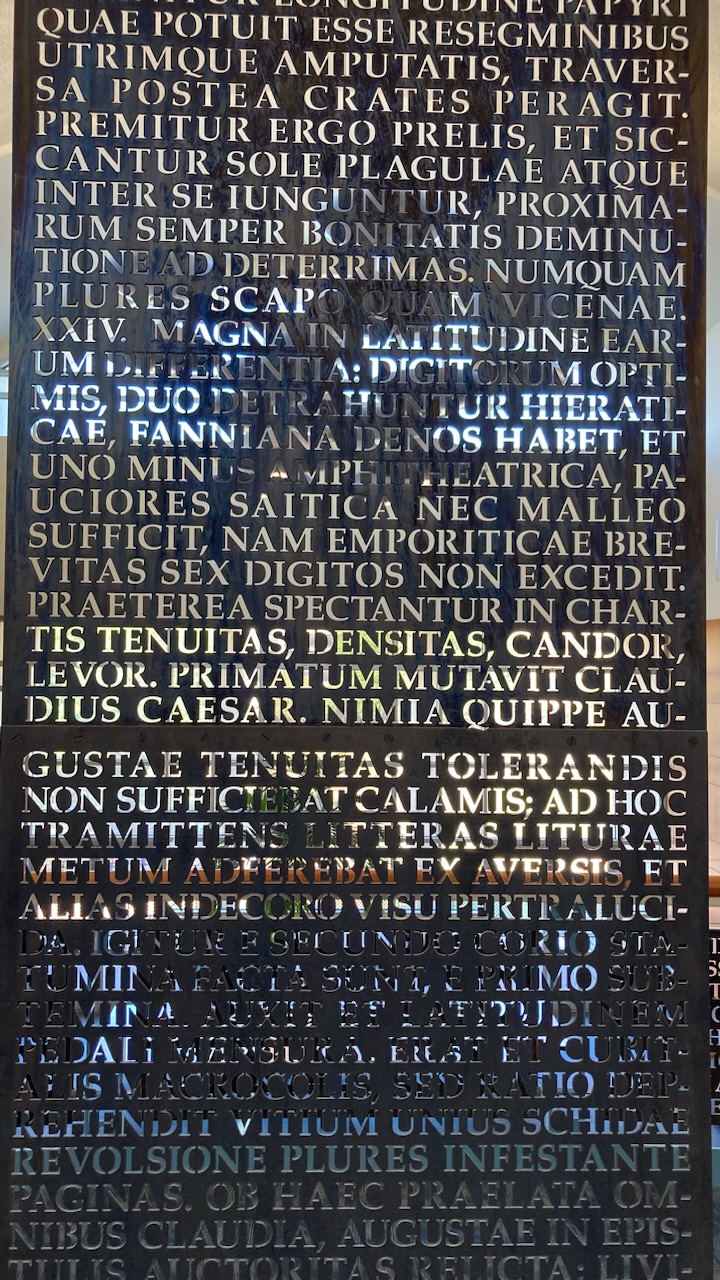

An impressive floor-to-ceiling steel scroll by the sculptor Jim Sanborn, has a fitting location on the mezzanine level of the M.D. Anderson library at the University of Houston. The scroll is constructed with cut-out texts excerpted from the classical Latin encyclopedia Natural History written by Roman historian Pliny in 77AD. The writings are direct excerpts from book thirteen (out of thirty-seven in all) detailing the history of papermaking and extolling the brilliance of the Egyptian craft born from that great civilization’s thirst for knowledge and education. Pliny’s writing shows that the Romans very much admired the wisdom and inventiveness of the Egyptians. Sanborn’s choice of five full translations and a sixth small inclusion (an excerpt within an excerpt) includes the history of papermaking, from the source of the material papyrus itself, to the types and qualities of various papers, to the names and origins of the different papers by regions, to the effects such a wondrous early technology has had on civilizations since. Pliny focuses much attention on the natural trees of the Middle East including entire sections on fig trees and palm trees. His focus is primarily upon Egypt with an intense interest in papyrus and paper making, with seven chapters devoted to the craft.

Situated among millions of books itself, the scroll reminds us that despite the incorporation of modern technologies into libraries and bookmaking, the book-form and language are early technologies that remain in use despite new inventions and “progress.” With a background in archeology, Sanborn highlights how our contemporary world forms a continuum with the ancients, reminding us that our own great civilization is built upon the shoulders of others, such as the Romans before us, and the Egyptians before them. We wonder what historical absences are left in the gaps from disappeared or destroyed texts throughout time (Pliny’s Natural History was the only book of his many volumes to survive).

With Pliny writing in Classical Latin, his words must be decrypted (or translated) to be understood, proving that language itself is a naturally encrypted set of drawn signs and signals—such as Egyptian hieroglyphics—that must be deciphered. Language is perceived as either natural to the reader’s understanding or it is encrypted if written in a language the reader does not understand. Sanborn’s sculpture is written in English, and translated from Classical Latin, now a dead language from the once great civilization. The artist shows us how precious such history and information can be—without the survival of the original text, or the capacity for translation, ancient history and knowledge would be lost forever. Pliny writes of the importance of the craft of papermaking and writing saying, “our civilization, or at all events our records, depend very largely on the employment of paper.” The scroll is a reminder of the presence of the great civilizations of Egypt and Rome in our own great civilization we live in today. The scroll also bears to mind the death of history’s two greatest empires–perhaps the artist’s own encrypted message to us all.

Located directly behind the scroll is another of Sanborn’s works, Fragments of Fiction (2003), created in the same style, addressing fictional works of literature as opposed to historical documents. Through addressing fiction and non-fiction the artist includes both genres—essentialized binary categories of “imagination” and “truth” that force texts into one tightly confined space. This maneuver by the artist directs our attention to the absence of texts belonging in between the “truths” and “untruths” and the many texts that transcend both categories. Upon reading both works closely, Fragments of Fiction and Pliny’s Papyrus soon reveal nuanced facts in the fictions and imagination in the historical writing, proving the two categories not nearly as binary as we are taught to believe.

Outside the library, upon entering the building, is another of Sanborn’s works, A Comma, A (2003) that collaborates with these two artworks. A Comma, A also addresses a varied global selection of fictional texts, primarily highlighting women writers and women as subjects. It likewise makes use of a light source—this one an artificial internal light source—to illuminate the texts onto the surrounding buildings and environments. All three of Sanborn’s works may be viewed together or individually.

Sanborn received his B.A. from Randolph-Macon College, Virginia, specializing in art history and sociology followed by his MFA from Pratt Institute in New York City with a focus in sculpture. For nine years he maintained artist-in-residence stature at the arts center of Glen Echo Park in Maryland. Sanborn has created public sculptures for Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Central Intelligence Agency, The Federal Reserve Bank, The Internal Revenue Service, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, along with many universities, arts institutions, and international American embassies. He has exhibited in numerous group and solo exhibits both nationally and internationally. Sanborn published a book, Atomic Time: Pure Science and Seduction (2004), concerning his artwork of the same title that was inspired by the Manhattan Project.

Location

University of Houston

MD Anderson Library, 2nd floor mezzanine