Adriana Corral

By Cammie Tipton, Assistant Curator, Public Art UHS

September 2022 | With an art practice based firmly in historical research, Adriana Corral (American, b. 1983) explores current issues regarding immigration, citizenship, human rights, and labor largely focused on the Texas-Mexico border. Born and raised in El Paso, Corral was early infused with a desire to investigate the histories of Texas and its relationship with its Latinx populations, especially as this point of contact related to human rights abuses, and themes of disappearance, memory, and erasure. Corral explains her work and her method when stating: “my work goes through a layered process, beginning with a conceptual framework that is dictated by the research I conduct. With a minimal aesthetic yet oftentimes loaded subject matter, I create installations, performances, and sculptures, that are solicitous composites of research, politics and universal themes of loss, injustice, concealment, and memory.” To achieve this, Corral works with research materials provided by anthropologists, journalists, gender scholars, writers, human rights attorneys, and victims. Working in richly organic materials such as soil, ash, paper, and cotton, Corral situates her theoretical work in a strong grounding of basic, earthy substances that help the viewer connect with the work on a visceral level.

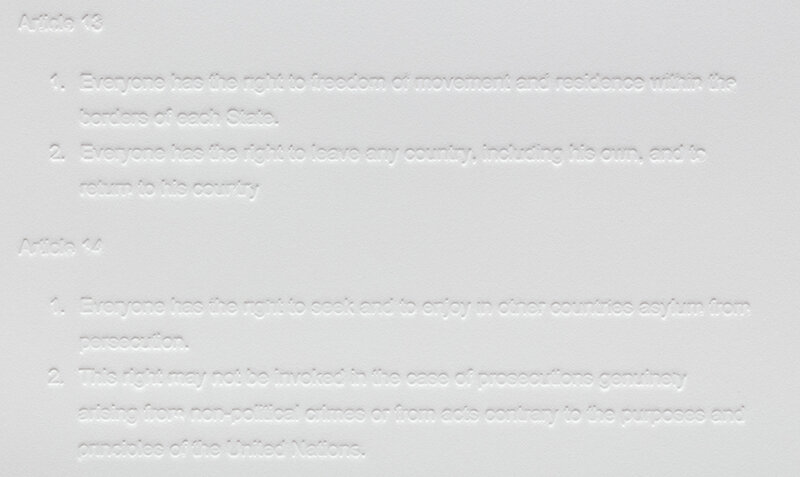

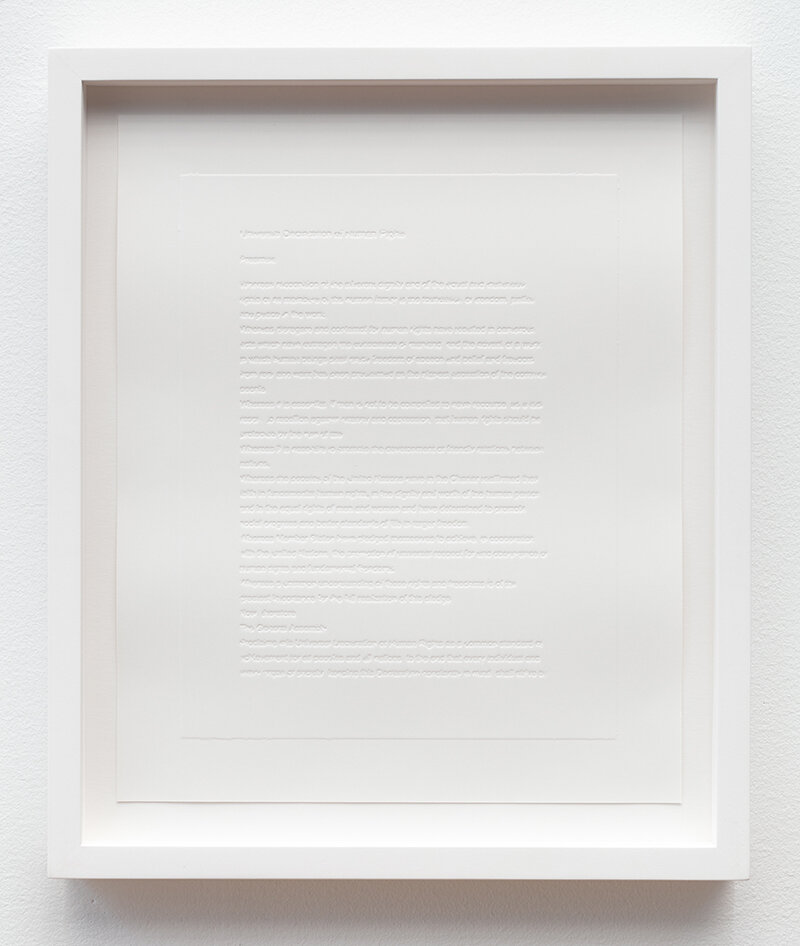

Latitudes (2016-19) is a series of multiple works on stark white paper, shrouded in white matting and white frames. In a ghostly fading, the artworks recede into the background, quietly excusing themselves of their presence, begging to not be seen. From a distance, the series of thick white sheets of paper appear to be blank pages. Corral prefers minimal techniques, forms, and materials in all her work, delivering soft tones and clean lines that slyly conceal intensely strong messages. Upon a closer view, we see the papers contain imprinted text in an official language and in an official form. The text is nearly invisible as it contains no ink. The text is created using a debossed form only visible because the impressed material yields to light and shadow. This un-text is language taken directly from the United Nations’ Declaration of Human Rights written in 1948. Corral has reproduced the language of the Declaration of Human Rights into English, German, Spanish, and Japanese. The nine prints in the collection of Public Art UHS are in Spanish, reflecting Corral’s own ancestral language, her interest in the historical interconnectedness between Texas and Mexico, and the thirty percent of the Texas population that speaks the language.

The stark whiteness of Latitudes is jarring—it disappears into the space around it. The words themselves are constructed to disappear—there is no ink here, only literal impressions that form shadows permitting us to see any wording at all. Words become empty form that take shape only by the ephemeral interplay between light and shadow. Shadows transform language into a ghostly apparition. For Corral’s work, placement of ink on a page is simply too normative a practice. Common ink placement is an act of simple layering, almost a caressing, of the page—and Corral has a very different message to deliver.

Latitudes is created using a debossing imprint technique, where a copper die-plate is formed that acts as a template for imprinting. The debossing process exerts intense pressure onto the material, forcing the paper to yield to its demands, creating a concave form. This concave form implies a hollow emptying-out of substance—a digging into the material that leaves a shallow grave. The title of the work, Latitudes, invokes Cartesian coordinates—lines and points on a map, cutting through space, that were created and utilized by European imperial forces in order to “know” and thus better control the globe. Global latitudinal lines (imaginary and invisible lines) reference the perfectly horizontal lines of the text, which, for Corral, are also nearly invisible and imaginary in another sense. However, ironically, this nearly invisible text is—according to law—permanent and very powerful. The seriality of the frames (a nearly identical reproduction) demonstrates the detached, mechanical function in which treatises such as the Declaration of Human Rights are produced. A removed committee, on another side of the world, through words and language, creates potential solutions for disenfranchised and struggling populations that can feel far too distant and utopian to be of any real consequence. Corral’s technique of easy repetition of the frames indicates hollow promises and easily dismissed proclamations.

Latitudes is more than a material art. It is a work that lives primarily outside of its material, in the realm of another artform—language. What do we want language to do for us? When faced with human horrors, why do we feel the need for language to respond? What can language achieve? What are the limits of language? Are the shortcomings of human beings inevitably connected to their language? These are some of the questions Corral asks in her work. The artist reveals to us the overarching structures that most impact our daily lives yet remain conspicuously hidden in our common experiences. Diplomatic and legal language—whether from the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights or state legislature or Supreme Court rulings—are artforms that directly impact our lives while remaining so intangible they are imperceptible. Corral attempts to close this distance between the rule of law and the people it affects. Language is simultaneously a connector and a disconnector. A foreign language or a language that one does not speak is another disappearance. When we read the words of a foreign language, we are alienated from the text. It does not speak to us, although we know it has meaning. This language-alienation is yet another obstacle people must overcome in order to belong to a place, a city, a nation, a population.

Corral created Latitudes between 2016 and 2019, a tumultuous time in recent memory, as immigrants—particularly Latinx immigrants, migrants, laborers, exiles, refugees, undocumented and citizens alike—were targeted in the United States for a perceived Otherness that was cemented with executive action. In January of 2019, an executive order titled “Border Security and Immigrant Enforcement Improvements” contained several sections undermining human rights and included the expanded use of detention, limits to asylum, enhanced enforcement along the US-Mexico border, and the construction of a border wall. Language is constantly morphing, with its emphasis refocused and redetermined through politics and cultural shifts. For all the United Nations’ good intentions in 1948, pleasant diplomatic language laid down in the Declaration of Human Rights was not enough to ensure future equality and justice. Knowing that we possess little control over such immense powers that manifest themselves in such simple acts as words on a page, Corral’s work forces us to question what can be erased and what is indelible.

The theme of disappearance—especially as it relates to the pale—is one that reappears throughout Corral’s work. In another artwork from 2018, Unearthed: Desenterrado, Corral creates a site-specific work in El Paso where she investigated the history of a former Bracero camp, a Mexican immigrant labor camp begun in America in 1942 to assist in agricultural production. Under the Mexican Farm Labor Agreement, Mexican laborers were invited to America to work the land while living in encampments primarily along the U.S.-Mexico border, at extremely low wages. Eventually, protests and strikes would lead to organized resistance. To engage with this complicated border history, Corral created a flag—that most prominent of national icons—that symbolized the history of the Bracero Program, and the El Paso site itself.

Constructed in purely white cotton and embroidered in white cotton thread, Corral’s design is composed of the American bald eagle and the Mexican golden eagle, struggling, and entangled with a snake. The flag was flown for three months, only to be ravaged by the elements, with the materials unraveling and deteriorating under the sun and weather. The flag points to the complexities of border-town identities and challenges our notions of boundaries, national symbols, and citizenship. A weather-beaten flag, deteriorating and disappearing thread by thread each day, reminds us that our memories of our history can vanish as quickly as a flag fades in the sun. However, Corral’s flag was pale—disappeared—from the beginning, perhaps indicating that our memories and our histories—especially of those populations under the control of national superpowers—never belonged to us to begin with.

The United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights was ratified in 1948 to ensure basic protections for the global population. The declaration was drafted by representatives from various legal and cultural backgrounds from all around the world and was translated into over five hundred languages. The text, written in that critical year of 1948, is a response to the unprecedented horrors of the Holocaust, and certainly speaks directly to the formation of the state of Israel from Palestinian territory in that same year, as well as the violent aftermath of the partition of India and Pakistan in 1947. In Latitudes, Corral helps show us that regardless of spoken intentions, written treatises, and diplomatic language, violence has not ceased, and it continues to proliferate in entirely new forms that leave victims less acknowledged and more invisible than ever.

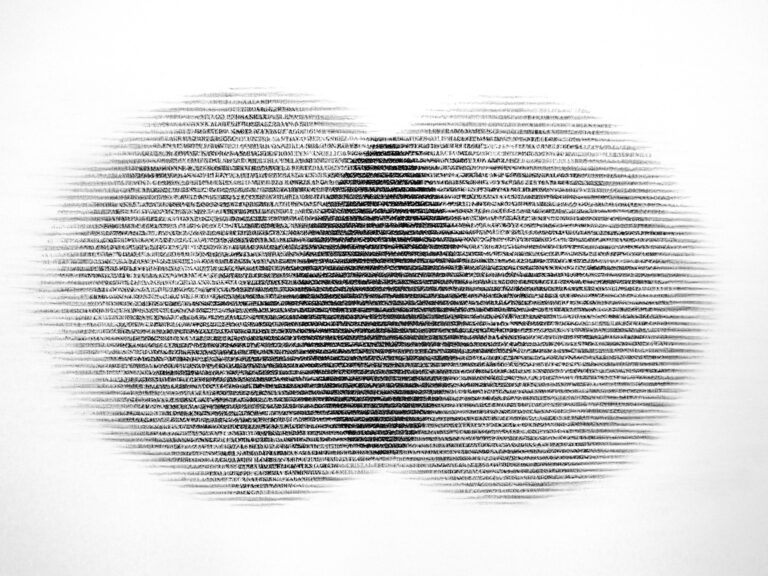

In 2015, Corral was invited to attend the United Nations’ Working Group on Enforced and Involuntary Disappearances. Many of these atrocities occur throughout Mexico in staggering numbers affecting families that eventually choose to seek asylum from narco-violence. In another work of Corral’s from the Public Art collection, the artist speaks directly to the victims of this violence in her work Impunidad, círculo vicioso [Impunity, vicious cycle] from 2015. The work is composed of the (barely perceptible) names of fifty one victims of violence in Mexico. In twin overlapping circles, Corral lists the names of a group of women victims whose remains were found in a cotton field in Ciudad Juarez on the left, along with a group of undergraduates and teachers who were burned alive and buried in mass graves by drug cartels on the right. The two images resemble overlapping full moons, eclipsed from the light. Corral’s imprinting technique is one of removal and transference. She types each name on an individual sheet of paper, then using a cotton ball moistened with acetone, places the paper and ink between the wall and the cotton ball. The acetone dissolves the ink, transferring it to the wall, as the ink bleeds through the paper. The forms are blurred, the names are nearly unrecognizable, and as the circles meet, the shadow darkens.

Corral’s experience at the United Nations made her acutely aware of the limits and outright failures of diplomatic language. She discovered that throughout political processes, the text, and the people it endeavors to save, are ironically both erased—disappeared—despite their best efforts. Many Mexican families fight in vain for justice. Some of Corral’s artworks include the names of victims of narco-violence and femicide that attempt to bridge the oftentimes imperceptible relationship between language (names) and human beings (victims).

Corral was born and raised in the border town of El Paso, Texas. She received her BFA from the University of Texas at El Paso and completed her MFA at the University of Texas at Austin. She was awarded a Harpo Foundation Award (2020) and the Artadia Award (2019), and she was selected for the Joan Mitchell Foundation Emerging Artist Grant (2016). Corral has participated in several artist residency programs including the McDowell Residency (2014), Künstlerhaus Bethanien Residency in Berlin, Germany (2016), the International Artist-in-Residence at Artpace, San Antonio (2016), and an Artist-in-Residence at the Joan Mitchell Center (2018). Fellowships include Black Cube, a Nomadic Art Museum (2017), the Archives of American Art and History at the Smithsonian Institution (2018) and the prestigious Mellon Foundation Latinx Artist Fellowship (2021). The artist has participated in several group and solo exhibits throughout the country. She lives and works in Houston.