Jim Sanborn

(American, b. 1945)

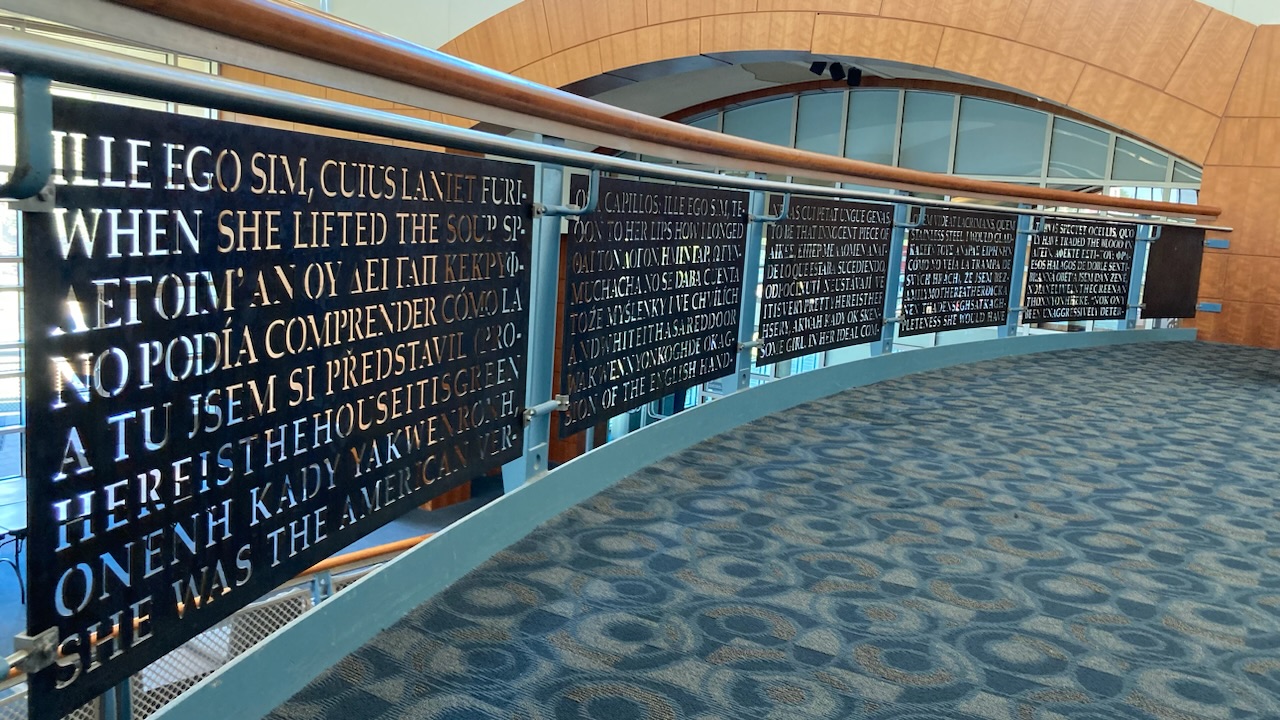

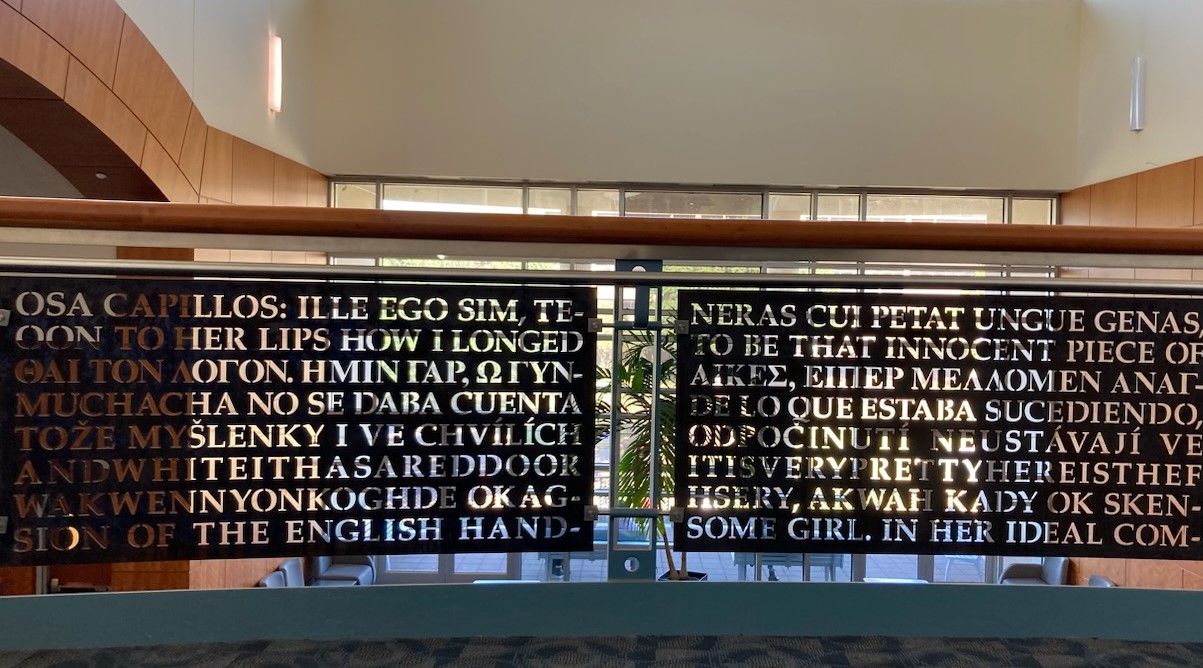

Fragments of Fiction, 2003

Bronze and copper

The sculptor Jim Sanborn has created a functioning steel railing located on the mezzanine level of the University of Houston’s M.D. Anderson library. The railing is also an artwork, titled Fragments of Fiction, and it displays eight horizontal lines of excerpted fiction from various global texts and languages such as Classical Latin, Spanish, Czech, Greek, Native American Iroquois, and English. This fusion of artwork and functioning architecture is simply another way in which the artist likes to combine and conflate elements of art—the aesthetic and the practical should not necessarily be separate. Sanborn explores fiction like an archaeologist delving into its workings and its histories. His installations force us to ask where the truth lies. Behind so many layers of absence and veils, viewers must perform their own excavation of sorts.

As we plainly view the text on the railing, we understand however, that it is a text chosen by the artist, written by the author, and voiced by the subject (who is a fictional character). All are ephemeral. The work unveils a palimpsest of voices (housed in the library among millions of voices) each with their own ideas and histories and objectives, making truths slippery. This practice forces us to ask who actually holds the knowledge we find in texts—the author or the subject or the reader? However, we remember that the railing is an architectural structure offering protection and security. The focus here is on fiction—a pretend world based upon reality. However, Sanborn shows us that reality and fiction are in fact cut from the same cloth. The imagination, combined with memory and creativity, ironically help us to understand our reality and our truths.

For this work, Sanborn carefully chooses global languages that represent shifts and changes, allowing an understanding of the flow of history. Six languages are present with lessons to be found in each. While English may assuredly be our present-day global language, it forms a neat opposition to Classical Latin which was the modern world’s first universal language. The inclusion of the Onondaga language, one of sixteen Iroquois languages originally spoken in the Northeastern United States highlights a language that is critically endangered with only a few elders still speaking the native tongue of the tribe. The inclusion of the Czech language represents a native tongue that, several times throughout history, has been on the brink of extinction—edged out by German invaders and later by the Soviet Union—surviving only by the fates of history. Also present is the Greek language, which was once a universal language from one of the world’s greatest civilizations and one of the world’s oldest written languages. Now, the Greek language finds itself relegated primarily within its own nation-state, shrunken in stature. Through all these examples, Sanborn shows us that language is very much alive, as much a living organism as any author or reader. Languages evolve and must withstand the struggles and triumphs of history as much as we all must.

Like Sanborn’s A Comma, A (2003) which stands alongside the library’s entrance, Fragments of Fiction is a display of women’s voices either from women authors or subjects. From the Roman philosopher Ovid’s satirical treatise on how to attract women, to contemporary American author Toni Morrison’s novel on the hardships Black women must endure, Sanborn has carefully chosen texts highlighting women’s place in global history as we understand it through the written language. At times, the artist presents us with the tensions between traditional binary sexes, but there also exists non-binary presences such as the inclusion of the voices of the authors Gertrude Stein and Jeanette Winterson’s sexual non-polarities. Similarly, the Iroquois text remains highly ambiguous in its reach, offering an almost cosmic approach. In these texts, women’s voices across the globe and throughout history remain a perpetual strength amidst deeply entrenched patriarchy. These eight lines of text can be read individually and performed on their own, or they can be read together as a collage forming Sanborn’s own “written” text.

Directly in front of the railing on the mezzanine level is another of Sanborn’s works, Pliny’s Papyrus (2003). The work, in a similar style to Fragments of Fiction, is an impressive floor-to-ceiling sculpture in the shape of an ancient scroll. These three works by Sanborn are perfectly situated to welcome students and guests into the library. All three of Sanborn’s works function collaboratively with one another while also remaining independent works to be studied in their own right.

Sanborn received his B.A. from Randolph-Macon College, Virginia, specializing in art history and sociology followed by his MFA from Pratt Institute in New York City with a focus in sculpture. For nine years he maintained artist-in-residence stature at the arts center of Glen Echo Park in Maryland. Sanborn has created public sculptures for Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Central Intelligence Agency, The Federal Reserve Bank, The Internal Revenue Service, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, along with many universities, arts institutions and international American embassies. He has exhibited in numerous group and solo exhibits both nationally and internationally. Sanborn published a book, Atomic Time: Pure Science and Seduction (2004), concerning his artwork of the same title that was inspired by the Manhattan Project.

Location

University of Houston

MD Anderson Library, 2nd floor mezzanine