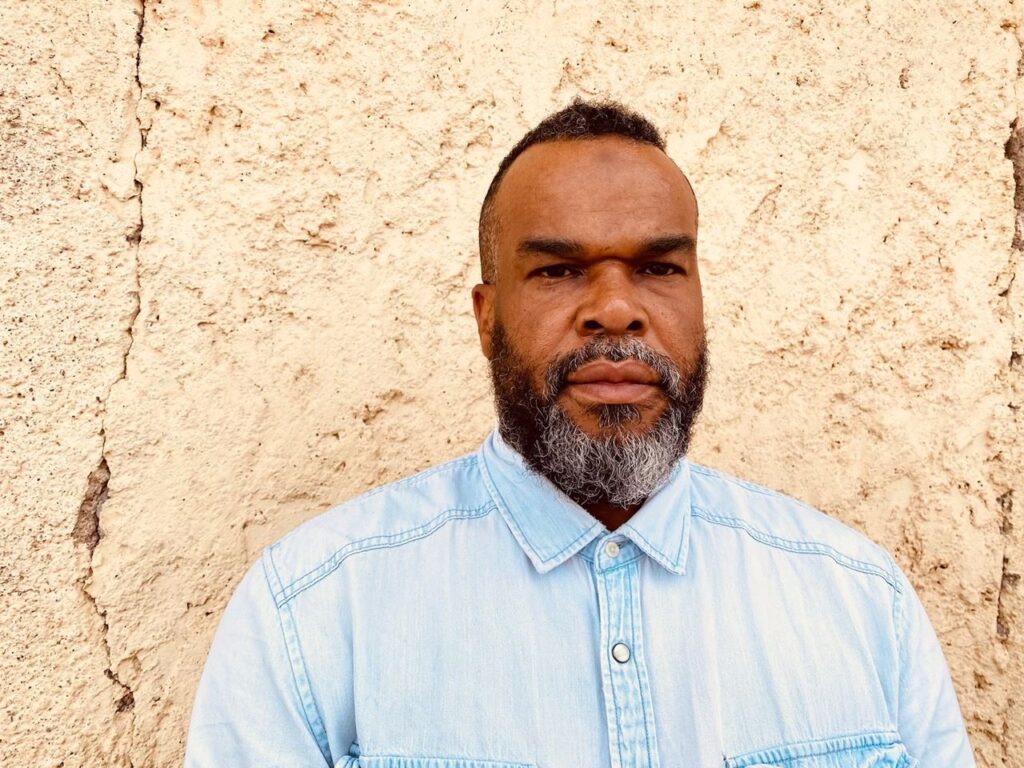

Jamal Cyrus

By Cammie Tipton, Assistant Curator, Public Art UHS

April 2022 | Houston-based artist Jamal Cyrus (American, b. 1973) draws us in and implores us to look closely at what is not there. His ongoing Eroding Witness series illuminates forgotten and erased histories of the local Black Power movement. While the larger liberation movements of cities such as Chicago and Los Angeles are historically more well-known and documented, Cyrus seeks to excavate rich local histories of resistance from the Houston and Third Ward communities.

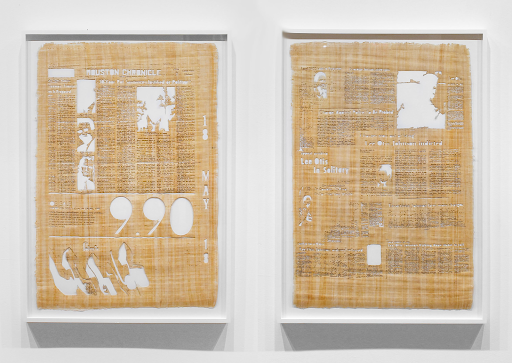

His diptych Eroding Witness, Season 3 Episode 20 (2018) is composed of two archival documents reproduced on laser-cut papyrus. The document on the left, from the front page of the Houston Chronicle, boasts the headliner article “30-Year Pot Sentence Justified or Political?” a clear sensationalizing of the arrest of local Black resistance leader Lee Otis Johnson. The corresponding document on the right is a compilation of shorter articles concerning Johnson’s sentencing and well-being after his 1968 arrest. Johnson, a leader of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in the 1960s, becomes the subject of Cyrus’ reawakening of local resistance leaders. While a student at Houston’s predominantly black Texas Southern University, Johnson led the 1967 TSU student strike and was a leader of the TSU riot, in which a policeman was killed and nearly five hundred students were arrested. In 1968, Johnson was arrested for giving marijuana to a policeman and was sentenced by an all-white jury to a prison term of thirty years. While imprisoned, the chant of “Free Lee Otis!” became a rallying cry for students and progressives across Texas who wanted drug law reforms and the promotion of civil rights. The popular slogan was featured on bumper stickers, T-shirts, and in local artworks.

In these works, Cyrus’ intention is to have us closely inspect and question official narratives and ask fundamental questions of our leadership. Various Houston newspapers covered the story of Lee Otis Johnson and others of the Black Power movement, each with their own perspectives, often with conflicting conclusions. In uncovering these forgotten voices of Houston’s own Black Power movement, Cyrus asks us to examine the stories that the city tells about itself.

Papyrus is a material rich in historical meaning, first used in the great African civilizations of ancient Egypt. Papyrus formed the earliest books and the first libraries and archives. Here, Cyrus highlights the noble legacy of civil education among Black populations, standing in stark contrast to modern systems that have repressed Black education for centuries. The artist declares, “Due to the illegality of teaching the enslaved to read and write, and the subsequent lack of access to education following emancipation well into the middle of the twentieth century, the action of teaching oneself has a long history within Black culture.” In Cyrus’ works, we must search for our own truths—a self-education—among erasures, absences, and lies.

In this series, the ancient and contemporary collide. Not only are present-day documents inscribed onto ancient materials, but even the techniques of modern lasers converge with the ancient craft of papermaking. The heat-wielding lasers cut into delicate papyrus, forcing a violent erasure, a permanent marking, that transforms the fragile materials of history. The series’ title, Eroding Witness, is based upon a set of poems by Nathaniel Mackey from 1986 focused upon black magic and shamanistic ritual. Within the title, Season 3 Episode 20, informs us that these works are a narrative series, full of suspense and riveting characters, that we consume as if binge-watching a new television series. With this method, Cyrus delivers an endless theater of forgotten and silenced stories.

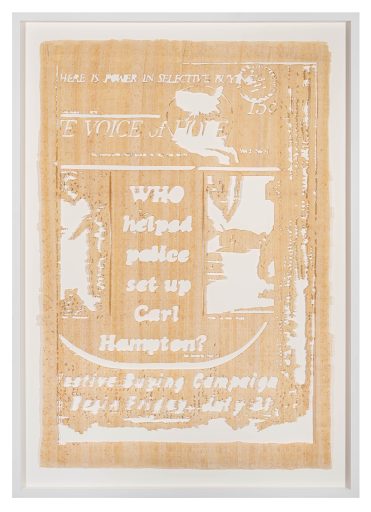

In Eroding Witness 7d (2014), another example from the series, Cyrus reawakens the young Houston Black Power leader Carl Hampton. Hampton had formed his own organization, the People’s Party II that acted as a precursor to Houston’s own Black Panther Party chapter, and was headquartered on what is today Emancipation Boulevard. Hampton was a charismatic leader invested in the welfare of the Third Ward and initiated programs distributing free food and medical supplies to the community. In the 1970s, Houston’s police department was directed by a known racist and was widely considered one of the most brutal policing organizations in the nation. In 1970, after a ten day standoff from the rooftops of the People’s Party II headquarters, Hampton, only twenty one years old, was shot and killed by Houston police officers.

In his visual investigation of Hampton’s short life, Cyrus describes the powerful role of media in not only disseminating information but diagnosing and determining an ultimate consensus. In this series, Cyrus shows how each local newspaper gave a different assessment of the incident, with some papers not covering it at all. When we cannot trust these media outlets, many times the work of unearthing the truth must be patiently done by us, and ironically may include oral histories from home, gossip from the streets, and narratives from friends and family who were present. Stories of local heroes emerge and Cyrus works to reanimate them, paradoxically preserving them by highlighting their erasures. Recording these stories as a popular television show, Cyrus warns us that Black America’s history—including the Black Power movement—has been commoditized and subsumed by popular culture and consumerism, further threatening their erasure.

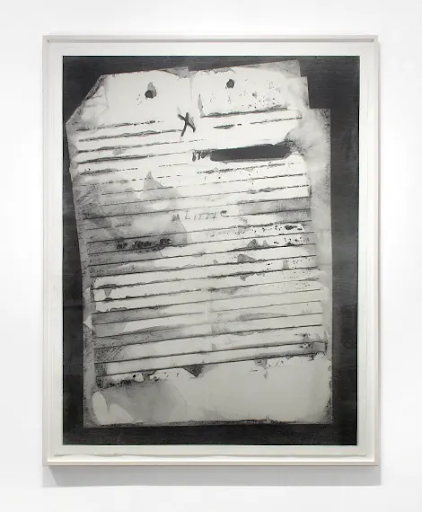

Cyrus works with any number of found materials such as vinyl records, wooden chairs, worn denim, and musical instruments. However, one constant throughout his career is his exploration of works on paper. Paper, as an art material, is ripe with paradox. Simultaneously delicate and resilient, ancient and modern, paper is a material whose surface has been historically used in the act of liberation through personal education (Martin Luther King’s letters from his Birmingham jail, Nelson Mandela’s prison notebooks, Black Panther handbills) and also as the act of oppression through governmental and cultural systems (FBI files, mass media, and textbooks).

In X Codex (2008), Cyrus has recreated, with simple pencil and paper, an FBI document from the surveillance of Black Nationalist Malcolm X. Primarily in the long 1960s, the FBI ran a counterintelligence program, COINTELPRO, covertly and illegally surveilling all matters of the Civil Rights movement and the Black Power movement among others. In his drawing, Cyrus highlights the obscurity and the sanctioned iniquity of these acts of oppression by rendering the entire document illegible. The larger black boxes obscure what we understand to be important text about Malcolm X, and while the purpose in obscurement is to conceal, the large black boxes only highlight what is not there and piques our curiosity.

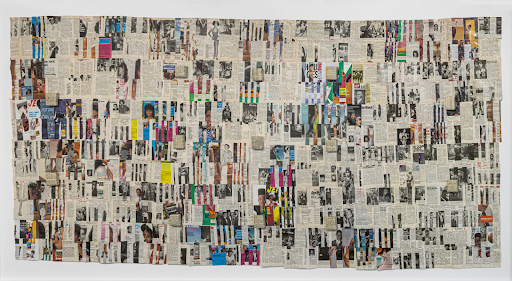

Jet Auto Archive, April 27, May 11, May 25, 1992 (Medicated L.A. Kente) (2018) is a brilliant example of Cyrus’ use of paper and repurposed materials. The large-scale work is woven from the artist’s personal collection of old Jet magazines. In 1992—the year Jet was published—Los Angeles erupted into violence after the acquittal of four police officers who repeatedly beat a Black man, Rodney King, all of which was caught on film by a bystander. The footage was continuously looped on national television and sparked local and national protests. In Jet Auto Archive Cyrus literally weaves the racism-fueled violent narratives of the Rodney King incident with capitalist-fueled cheerful narratives of Jet magazine’s advertisements. The two juxtapositions reflect the confusions of a Black population navigating how to live in a nation perpetuating the brutal legacy of systemic racism within a capitalist structure that seeks to pacify those same anxieties and fears it creates with the easy lure of commodities. The weaving technique in this piece is based upon the traditions of Kente cloth weavers of West Africa, who use silk and cotton fabric to visually tell stories of their culture and heritage in the patterns they inscribe in these cloths. In this collage, Cyrus does the same, by forming a complex conversation about where power lies and where resistance must mount, not only in our governmental systems, but equally in our economic and cultural systems.

Slyly advancing valuable lessons through an examination of the local archive, Cyrus shows us that when we use a patient eye, we discover that what is not present tells an equally important story as what is present. His art is a practice of revealing what is absent. Looking at and contemplating these erased histories rightly generates feelings of anger and sadness; however, it is that same emptiness—that void—that also miraculously leaves a blank space, ripe for rebuilding, restructuring, and revisioning. In this, Cyrus ultimately leaves us with hope.