Rick Lowe

By Cammie Tipton, Assistant Curator, Public Art UHS

Returning to a painting practice after years of success in the field of social sculpture, Houston-based artist Rick Lowe presents us with abstract canvases that reimagine much of the work he has been committed to for over thirty years. Primarily working in social sculpture—a practical interface between art and community development—in Houston’s historic Third Ward, the artist has now turned his attention to the two dimensional plane. As a founding member of the highly distinguished Project Row Houses in Houston, practical issues of gentrification, community enrichment, and poetic Black spaces are always forefront in the artist’s mind. Over the decades, as artistic practices have shifted away from the two dimensional canvas and into everyday life, the artist’s recent transition to the more traditional medium of painting seems to beg the question: what is painting capable of now? Specifically created for Public Art UHS and the recently inaugurated John M. O’Quinn Law Building, The Line (2023) is an investigation into the spatial, cultural, economic, and everyday demarcations between Houston’s Third Ward community and the University of Houston campus. The work helps us to explore how and why such delineations are formed, who they serve, who they disenfranchise, and what possibilities exist beyond boundaries.

The Line

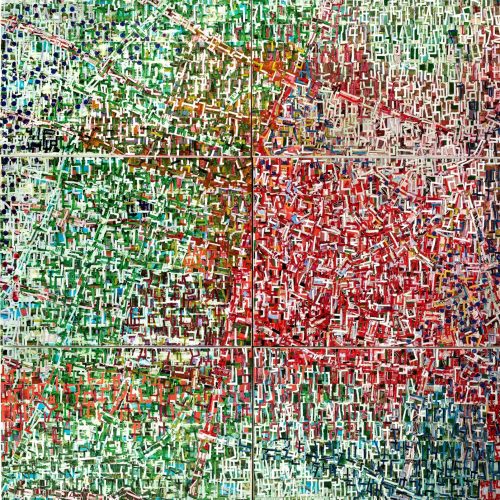

Lowe’s larger paintings (such as this one, composed of six panels affixed together) give us unique viewings from three distinct distances: far away, middle distance, and very close up. From each of these vantage points, the painting makes compelling shifts, introducing us to a seemingly new canvas as details slowly reveal themselves to recreate the work anew before our eyes.

From a distance, the bright contrasting colors of red and green form a dynamic combination. These two colors—with their opposing places on the color spectrum—create a visual electricity when placed side by side, generating a kinetic energy. The bright red appears to bleed across the canvas, fluidly forcing an intermingling and creating shifting spaces. The canvas holds an incalculable number of short, sharp white lines, marking every inch, and appear like scrambled vertical lines of programming code or perhaps the visual language of hieroglyphics. The painting’s composition and structure reveal a map-like arrangement and our imaginations immediately attempt to locate a place in the representation. At this distance, the image bears a striking resemblance to an urban city grid viewed from the passenger window of an airplane—the location seems familiar but you cannot put your finger on it. With a sense of frustration we try to decipher the coded language and the place before us, but we cannot identify what is being communicated. Sign and signal are disrupted.

Moving in closer to the middle ground, patterns and textures begin to appear, allowing depths and dimensions. Patterns of lines—wavy and straight—form byways resembling streets, bridges, freeways, paths, and other connective networks. We distinctly see the individual cutout shapes of paper that have been painted over several times, some torn away, distressed, then collaged together. These hundreds of cutout papers resemble classic mosaic patterns, whose individual pieces mean little, but when carefully arranged together reveal a greater story. The stark white lines, jutting in every direction, invoke the Minimalist sculptor Sol LeWitt’s incomplete cubes that remain open so as to incorporate all the space around them forcing the viewer to question what we think we understand about form, space, and enclosure.

As we move in very closely, only steps away from the canvas, a new world emerges as we notice small reproduced images that begin to surface from in between the cutout papers and underneath the paint. Fragmented images of such Third Ward educational institutions as Yates High School and the historically Black Texas Southern University appear in the green areas while images of the University of Houston’s logos and seals appear in the red areas. Our location is specified. As we move closer to the level of micro-viewing, we catch glimpses of images from long ago, of people—such as the University of Houston’s first Black Homecoming queen and activist Lynn Eusan—and local landmarks that seem to rise up from the depths of history like hidden clues beneath the surface. These images contain personal stories embedded in the foundations of a place, peeking out at us, reminding us that our recent past is rich and located only a few layers away from our present. Our eyes search these images with the feel of an archeological dig. Unlike programming code or hieroglyphics, these tiny reproduced photographs are highly legible, revealing local and personal histories that shape who we are today.

Lowe explains that he formed his compositions from his love of playing dominoes. A social game that brings community members together, when played, white domino tiles form growing lines, sprouting like vines, with each game resulting in distinct visual patterns. The artist begins his canvases by painting dominoes patterns on large sheets of thick paper, then cutting these sheets into smaller pieces (approximately the size of dominos themselves), then collaging them in unspecified patterns along with various materials and images onto the canvas, and finishing with more painting and distressing the surface. The result is a complete artwork created from many layers of constructed connections built upon a strong historical foundation.

Maps

Maps have permeated Lowe’s life for at least thirty years. Since the inception of Project Row Houses, the artist has been deciphering maps of urban planning, real estate, home ownership, land use, etc. Unsurprisingly, his recent canvases display (perhaps a subconscious manifestation) a remarkable resemblance to urban maps. As cosmopolitan cities have grown into highly desirable living spaces in the last century, minority communities that have populated urban areas for generations have been subject to displacement, whereby housing prices and taxes are raised to such an extent that locals cannot afford to live in their own neighborhood any longer. Not only does this force locals to relocate, but personal histories are lost, forming yet another layer to historical acts of displacement and erased histories of people of color. Lowe explains his motivations saying, “There are no clear set answers to issues like gentrification or black economic investment…so paintings help settle me a little because sometimes these things are about questions and not about answers.”

In addition to gentrification, systemic forms of displacement of minority groups come in many different forms. Lowe’s colorfully sectioned maps also recall the racially motivated discriminatory act of redlining that developed in early American urban planning. The act of redlining involves physical maps marked up in order to distinguish areas considered worthy of investment and areas—mostly of Black and minority populations—considered not worth investment. These historic maps, found in archives today, distinguish racial and ethnic minority neighborhoods by different brightly colored sections. In the 1930s, as Houston was expanding its urban infrastructure, the practice of redlining districts included the design and placement of freeways specifically built along redlines in order to maintain racial segregation. Yet another form of racial discrimination that necessitates maps is the manipulative political districting act of gerrymandering. In this, state districts are redesigned every ten years after the census results—by drawing lines and colors on a map—and are frequently manipulated by an incumbent political party to affect its desired outcome. This practice results in minority communities not receiving fair representation from their elected officials. These powers of decision making in socio-politics employ the use of physical maps, therefore, in order to push back against systemic power, a thorough understanding of maps and all their uses is necessary. As the French psychoanalyst Franz Fanon remarked, “Mastery of language affords one remarkable power,” and the language of urban spaces is maps.

In making The Line, Lowe’s ongoing interest in his own neighborhood of the Third Ward continues. The notion of “the line” in the title refers to an invisible (but mapped) designation of Scott Street as the official demarcation between the Third Ward and the University of Houston. While living and working in the Third Ward as well as working at the University of Houston as a professor in interdisciplinary practices, the artist inevitably bumps up against the tensions and discrepancies between these two areas. While the Third Ward struggles to sustain itself and its identity among growing gentrification, the spaces of the University of Houston are rich in intellectual and economic development. The Line explores how one slant invisible space of a line (and a city street) is used as a tool of segregation, marking inequities and racial discriminations for generations of people. Lowe’s hope is that his painting will offer “an opportunity to think about the issues of equity and urban planning in a more conceptual way.”

Project Row Houses

How do you do the impossible thing? It is a question that inspires the best artists of our time. In 1993, Lowe and six creative friends had a vision to elevate a seemingly disposable thing (the ubiquitous shotgun or row houses of the Third Ward), through a magical transformation (hard physical labor), into a wondrous place (a rejuvenated and sustainable Black space of prosperity). They called the endeavor Project Row Houses, and they transformed seven derelict shotgun houses into a vibrant cultural district, proving the ability of Black urban neighborhoods to sustain themselves and their heritages while pushing back against both demolition and gentrification. After generations of the erasure of Black homelands with the European colonization of Africa, American slavery, discriminatory reconstruction practices after the Civil War, and contemporary systemic racism and human rights violations, Project Row Houses is more than social sculpture—it works as a historical redressing of the erasure of Black spaces, a building of Black architecture, and a claiming of ownership of community grounds and lived experiences.

Lowe’s earliest inspirations—ones he is always sure to give credit to—are the German conceptual artist Joseph Bueys and Lowe’s personal mentor the Houston muralist John Biggers. Both men were outstanding artists, conceptual thinkers, social justice advocates, and highly respected teachers. Both Bueys and Biggers taught that the artist can affect socio-political change through artworks that are both visual and practical. Similarly, Lowe can be placed in the long history of historical Black thinkers who have investigated spatial theories and practices in the twentieth century. The American sociologist and writer W.E.B Dubois explored reconstruction in the United States following the Civil War, and illuminated the systemic removal and segregation of Black spaces despite the ratification of the thirteenth amendment. Reconstruction (literally, “to construct again”) meant that the building of new neighborhoods, cities, states, and legislations after the Civil War could allow Black populations a chance at a rebirth and renewal. However, the maps and plans drawn for the rebuilding were constructed with purposeful segregations and absences. Dubois’ purpose in focusing on America’s reconstruction is to illuminate those invisible racial agendas whose effects are seen in our built environments, and to illustrate how these built environments help form our perceptions of other human beings. Similarly, the French psychoanalyst and writer Franz Fanon acutely understood the oppressive purposes of French colonial architecture in Algeria. These built environments were used to control colonized populations and Fanon wrote clearly about the carefully built bridges that both connected and separated locals from the settler colonialists. Fanon’s awareness of the many architectures of control—walls, ports, narrow streets, bridges—highlighted the colonizer’s use of the built environment as a tool for surveillance, segregation, and control. Great thinkers who investigated the intersections of social space, the built environment, and social justice–from the French philosopher Henri Lefevbre to the Black Panther Party—each understood the complexities of human bodies interconnected in space.

The Return of the Object

After a successful career in social sculpture, why shift to the two dimensional canvas now? The move from the practical to the conceptual may seem like a reversal or perhaps a squeezing of space instead of an expansion. It is certainly an odd redirection from the exciting relational aesthetics of the twentieth century, to more traditional Cartesian mapping of the seventeenth century. The change, however, seems to be an extension of the work Lowe has been practicing for decades, and the canvases form a new method of investigation into ways to bring people together. The artist explains that making a painting “is almost like building a community in a sense, because you have to make connections, layers, build upward from nothing. It’s geographic, psychological, and social.” Can viewing an object on the wall effect change in the same way as lived participation in the built environment? After thirty years, Lowe seems to understand that built structures are immobile and many of his projects are temporary, while the art object is portable and (mostly) timeless. Not everyone is able to visit the Third Ward, Houston, or the Greenwood Art Project in Tulsa, therefore, the artist offers an object (a portable commodity) that acts as a visual representation of his larger work. He describes his motivation behind creating paintings as an interest in constructing “archival pieces,” or works of art that reference previous temporary projects. For anyone who did not get the chance to experience these temporal environments, there is now a material object to guide the viewer through the conceptual underpinnings of the initial project. From deciphering maps and painting houses to creating maps and painting canvases, the act of painting is the latest evolution of the creative community work Lowe has been passionately involved in for over thirty years.

Rick Lowe was born in 1961 in rural Russell County, Alabama, and currently lives and works in Houston. Solo exhibitions include Art League Houston (2020–21); Meditations on Social Sculpture, Gagosian, New York City, (2022); Notes on the Great Migration, Neubauer Collegium, University of Chicago (2022). He has also participated in Documenta 14, Athens (2017) and was included in the Whitney Biennial (2022). Among Lowe’s numerous community art projects are Project Row Houses, Houston (1993–2018); Watts House Project, Los Angeles (1996–2012); Borough Project (with Suzanne Lacy and Mary Jane Jacob), Charleston, SC (2003); Small Business/Big Change, Anyang Public Art Program, Korea (2010); Trans.lation, Dallas (2013); Victoria Square Project, Athens (2017–18); Greenwood Art Project, Tulsa, OK (2018–21); and Black Wall Street Journey, Chicago (2021–). His works are included in such collections as the Brooklyn Museum, New York; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami; High Museum of Art, Atlanta; Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art, Overland Park, KS; Menil Collection, Houston; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; and the UBS Art Collection. In 2013 President Barack Obama appointed Lowe to the National Council on the Arts, and in 2014 he was named a MacArthur Fellow. He maintains gallery representation from Gagosian in New York City. Lowe is currently a professor of interdisciplinary practice at the University of Houston.