Survival and Growth in John Biggers’ Salt Marsh

By Allison Young, Curatorial Intern (Fall 2023), Public Art UHS

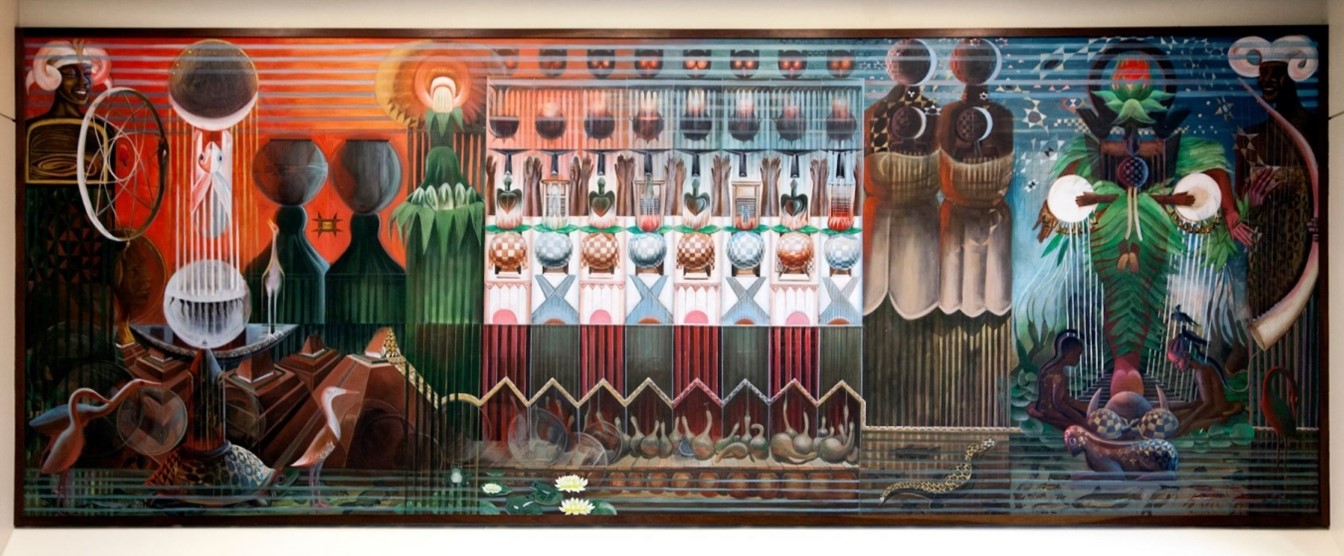

The artist John Biggers viewed art as less of an individual expression and more of a responsibility to the public due to its power to “reflect the spirit and style” of Black Americans. These attitudes mirrored the leadership the artist attained in the world of art and academia. Biggers was responsible for founding the Art Department at Texas Southern University in 1949 and his contributions to the Houston art scene are still visible through generations of Black artists. Although he worked in drawing, painting, and sculpture, Biggers is most recognizable for his mural projects spanning across his career. These murals—found across the country with numerous examples in Houston—both criticize the unjust realities faced by African Americans and illustrate connections with African cultures. His visual language uses motifs and symbols from these cultures to create positive representations of African ancestry for Black Americans. Salt Marsh was commissioned by Public Art UHS for the University of Houston-Downtown and was one of the artist’s last murals, completed in 1997. Although utilizing his visual language, it is a unique divergence from his other works. Salt Marsh employs previously unseen motifs from Native American cultures and the Houston bayous to emphasize the artist’s concerns for cultural and environmental awareness on the diverse student population at University of Downtown-Houston. It remains a hidden gem in his mural projects, though these diverging characteristics are why Salt Marsh is a remarkable synthesis of Biggers’ ability to create stunning and reflective public works of art.

The boldly colored atmosphere of Salt Marsh demonstrates the artistic transformations that emerged following Biggers’ retirement in 1983. Having evolved from Social Realism to abstract and geometric representations, this period consisted of moments of experimentation. What were previously identifiable environments became abstract spaces contained by the canvas, covered in checkerboard and star patterns. This period also reflected his fascination with visualizing the concepts of rebirth, transformation and ascension, often emphasized with West African symbolism. Salt Marsh proves how effectively Biggers operated in these stylistic and thematic changes, and how he incorporated these artistic elements to broadcast important messages to his audiences. This mural creates a transcontinental, multicultural environment where man, spirit and nature live connected. With this imagined world, Biggers urges the importance of children learning about their cultural heritage, their environment and themselves. Through this self-awareness, children fulfill their potential of being what the artist describes as “our salvation and our hope for tomorrow,” ensuring the survival of culture.

Following this significance of children, Salt Marsh was partly inspired by an African children’s story about the turtle and the rabbit. Unlike the Greek fabulist Aesop’s version that teaches us that “slow and steady wins the race,” this story tells of the two animals caught in an endless chase. In West African folklore, the turtle represents the sun, and the rabbit represents the moon. This story then offers an explanation of celestial changes through familiar creatures. As dawn changes to dusk—seen in the bright orange and soft blue of the mural’s background—time marches on, and the turtle and the rabbit continue their chase.

Further emphasizing the cyclical nature of time, both animals appear throughout the mural regardless of their timely associations. To the left of the mural, indicating daylight, the rabbit is shown ascending with lateral lines from a full moon into a crescent moon, representing the lunar cycle. The full moon may also be a pool of water, as there are tadpoles seen swimming near the surface as if to follow the rabbit’s journey.

A group of children, confined in a rectangular section of space, occupy the center of the piece. Just like the tadpoles, the children reach with a wish aimed skyward as they extend their hands above their heads. This brightly colored section of the mural contains a host of images and patterns frequently seen throughout Biggers’ work. It also synthesizes the emphasized importance of children learning about themselves and their backgrounds. The group of children stand above the zigzagging roofs of shotgun houses – a structure intimately tied to Houston’s Third Ward community and Biggers’ own childhood. Their heads are covered in a checkerboard pattern, which Biggers believed represented mankind’s presence in the world through its geometry and meeting of right angles. A lotus flower blooms from each of the children’s head. These are an excellent example of the multiple meanings hidden throughout Salt Marsh. The flower in bloom can represent the growth of the child, physically and intellectually. It also references the native flora seen in the Houston bayous and suggests the ancient Egyptian symbol of rebirth.

The children reach their arms above them toward the heads of owls, objects that appear more as relic than realistic. This imagery embodies the wisdom to be gained as they grow into themselves and their communities. The owls are also the handles of combs – the teeth fit in with the other lines running vertically and horizontally across the mural. Combs also operate in Salt Marsh as the abstract bodies of the mothers and children positioned to the right of the owl-combs. These items possess a dual significance to African and American cultures as symbols of cultural and self-determination, most apparent with their usage during the Black Power movement in the 1970s. The incorporation of artifacts such as these into Salt Marsh illustrate the artist’s interest in these collective histories.

The comb-mothers carry their children on their backs, what many cultures’ women have done throughout time. The pairs are crowned in a checkerboarded head doubling as a crescent moon. Just like the rabbit, mothers and femininity are also intertwined with the symbol of the moon in many African traditions. These comb pairs that are only one of the representations of mothers displayed in Salt Marsh. A myriad of artifacts from African and American origins draws on the artist’s attention towards motherhood, as Biggers constructed numerous works throughout his career that emphasize his belief that “women are the creators of culture and civilization.” From an early age, Biggers recognized and deeply respected the labor and love that Black women contribute toward the continuation of family and community. He initially recognized this when he would assist his mother with her laundress duties. Household appliances, often utilized by women workers, such as kettles and washboards, emerge in the mural as symbols of rebirth and renewal. The artist described kettles as spaces for transformation, similar to the womb, while washboards are instruments of rejuvenation.

The gourds found underneath the shotgun houses further reference African cosmology and African American folk songs. They rest atop a balaphon, which the artist identified as a West African instrument similar to a xylophone. African folklores regards the instrument as creating sounds like the “music of the womb”—the heartbeats acting as the first rhythms heard prenatally.

Undoubtedly, Biggers emphasizes the importance of women as he does children to the collective growth of society. This resonates considerably in the ascending flight of a mother and child on the far right. The mother’s body—partially hidden by the overgrowth of ferns and leaves—acts as a guide for her child. Her child levitates with their arms outstretched to their side, a representation that Biggers often used to illustrate “the possibilities of children, their freedom, their innocence, and their ability to move skyward.” An abstracted symbol of the turtle with a flowering lotus nearly touches the child’s head in their flight. The symbolism that Biggers uses in his murals illustrates the beauty of ancestral traditions and their survival and transformation on American soil. It changes a work like Salt Marsh into a painted space of celebration and reflection on cultural and racial heritage.

Although the maturity of his abstract style would become more apparent later in his career, Biggers had been exercising different representations and symbolism ever since his travels to West Africa in 1957. He was awarded a fellowship with UNESCO (United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization) which permitted him to study first-hand the cultural traditions of Ghana, Nigeria, Benin, and Togo.

At this time, he was one of the first African American artists to visit Africa and would afterward become one of the first to then visualize connections between African and African American cultures through art. Biggers had described the six month expedition as shocking yet profoundly inspirational. He published a book, Ananse: The Web of Life in Africa, following his return to the U.S. which contains his own writing and drawings from his experiences. With his accounts he wished to “portray what was intrinsically African.” Biggers would return to Africa on a few more occasions throughout his life and would generate a personalized collection of artifacts and sculptures that acted as infinite sources of inspiration.

Despite his unquestionable talent, Biggers had not initially planned on becoming an artist, much less be a founder of an art department at a Houston, Texas college. His original aim was to become a plumber when he arrived at Hampton Institute (now Hampton University) in 1941. However, his enrollment in an art class taught by Dr. Viktor Lowenfeld would redirect his path. Lowenfeld, an Austrian Jewish refugee who fled Nazi persecution in 1939, introduced his students to African and African American art. Learning the historical and social context of African artifacts and seeing how contemporary Black artists were expressing their personal and racial identity completely altered Biggers’ worldview and his career. He began studying art and his education exposed him to works from Mexican muralism and the Harlem Renaissance. He briefly worked as a studio assistant to Charles White and Elizabeth Catlett, both African American artists and teachers at the university. He later followed his mentor Lowenfeld to Pennsylvania State University where he earned both his bachelor’s and master’s degree in Art Education in 1948. The following year he moved to Houston, Texas with his wife Hazel after being invited to be the founding chairman of the Art Department at Texas Southern University (then Texas State University for Negroes). It was here when he expanded his own art career and that of his students, providing a space for the same influential teaching that Dr. Lowenfeld had offered him. He even initiated a program shortly after the department’s founding that required senior art majors to paint a mural in Hannah Hall on the Texas Southern campus—a program that still operates today.

In Salt Marsh, the message of cultural preservation and importance of community is not limited to the finished product, as the progress incorporated many helping hands. Biggers, who was in declining health during the time of painting but still adamant on completing this project, was aided by Harvey Johnson and James McNeil. The large-scale, immersive artistic process drew a number of interested bystanders, who Biggers invited to participate in the mural’s completion. He did not mind the stylistic differences, stating that everyone’s participation would “bring them into the feeling of the whole thing.” The collaborative production is evidence of how Biggers, even in his retirement, never stopped teaching and never forgot his own education. When the mural was completed, with the help of the impromptu artists, Biggers engaged University of Houston-Downtown students to add elements in the water. Susan Davidson painted the catfish and frogs, Mujeet Rahman painted the water lilies, and Tizano Hernandez painted the birds.

Using university students’ help in painting various animals of the Salt Marsh ecosystem reflected an aspect of the mural that renders it unique against his other works.

The ecological elements of Salt Marsh are intimately tied to Biggers’ themes of rebirth and the cycles of life. The water that flows throughout the bottom of the work is a symbol of rejuvenation across numerous cultures. The water lilies are in various stages of bloom. They are in different parts of their life cycle. The fish and crocodile both represent life to the artist and acts as a reminder of the natural order of life forms in our world. This environmental perspective is also site-specific. The University of Houston-Downtown campus is nestled in what is regarded as the birthplace of Houston. In this location, the bayou converges with the railroads and highways, all contributors to the growth of the city. Biggers saw this as a site in need of attention. The regenerative powers that the bayous have long provided the land are dwindling, as “it is a salt marsh being poisoned by industrial pollution.” While this emphasis on environmentalism was new for Biggers’ work, he always painted what he believed needed to be known. Once again, a necessity for awareness is being proclaimed from the motifs and symbols in the work. Biggers wanted the students to become aware of their place within their environment by referencing the landscape just outside their classrooms. Not only does he stress a concern for the survival of culture, but the survival of the ecosystem.

The inclusion of Native American imagery a unique addition to Biggers’ oeuvre aside from House of the Turtle (1992), a mural painted at Hampton University in North Carolina, and which touches upon its enrollment of African American and Native American students following the Civil War. In Salt Marsh, however, the inspiration to represent Indigenous motifs came from the artist reading Of Water and the Spirit (1994) by Malidoma Patrice Somé. Biggers stated that the book—a biography accounting an African shaman’s journey in reconnecting with his tribe’s traditions—urged him to “visualize in mural form [his] reaction and concern” for both the physical and cultural environment. He resonated with a passage about colonization, particularly with the suppression of Indigenous American culture. “…As soon as one culture begins to talk about preservation, it means it has already turned the other culture into an endangered species.” Even in early drafts of the mural, Salt Marsh reflected on the threats of losing hereditary roots for both indigenous and diasporic communities. This is illustrated in the left side of the piece. Two clay vessels, each unique from each other, appear like those constructed by both Native Americans and Africans. A radiant sun—dually acting as a sunflower—encourages the growth of stalks of corn, a celebrated symbol considered to be the sustenance that allows life to grow. Their stalks become another addition to the multiple lines running across the work. Pyramidal structures near the base of the mural could allude to monuments found throughout the Americas as well as those in Egypt. Buffalo nickels—coins that feature the American buffalo and a profile of a Native American man—are nearly transparent yet still occupy the space. The sun deity that guards the left of the mural holds a dreamcatcher, representing an artisanal act of solidarity. The indigenous word for these artifacts, asabikeshiinh in Ojibwe, refer to the net-like structure, consciously chosen for its imitation of spider webbing. In the center, minute in presence, is a spider, further drawing a parallel between Native American and African cultural traditions. To the Akan people of Ghana, a group that Biggers became particularly attached to after his travels to West Africa in 1957, the spider—or ananse—is viewed as a trickster yet a direct messenger of God. Following folklore, ananse—hosted here in a cross-cultural web—demonstrates how such a small creature can create something beautiful and impactful.

Salt Marsh presents a sense of urgency that Biggers has left in the hands of the community and the students at the University of Houston-Downtown, though the message is relevant outside its locality. “As our children discover self-awareness,” Biggers stated, “we also find a mirror image for all of us.” Such revelations are not restricted by age, as Salt Marsh acts as a space of reflection for viewers, reminding us of the growth that we all must go through to be better for our communities and our world. The mural is also evident of the artist’s own awakening to these concerns and how he effectively adapted his artistic language to portray these messages. Citing an African children’s story, the bayous of downtown Houston, and a literary reminder of how culture has been endangered in the past as sources of inspiration, Biggers harmonized multicultural symbols and stories into an abstract landscape to encourage viewers to preserve the past for the sake of the future. After ensuring the survival of culture and the environment, an ecosystem like Salt Marsh may become a reality.

John T. Biggers was born in 1924 in Gastonia, North Carolina. He attended Hampton Institute before transferring to Pennsylvania State University, where he would receive his master’s and doctoral degrees in 1948 and 1954 respectively.

He moved to Houston, Texas in 1949 where he founded the art department at Texas State University. He was granted a fellowship with UNESCO in 1957. Other awards include the Purchase Prize, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (1950); Neiman Marcus Company Prize, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas (1952); Pennsylvania State University Distinguished Alumnus Award, University Park (1972); and Texas Artist of the Year, Houston (1988). He was featured in solo and group exhibitions across the country, including Young Negro Art, Museum of Modern Art, New York City (1943), and The Art of John Biggers: View from the Upper Room, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (1995). His work is part of museum collections such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Brooklyn Museum, Museum of Fine Art, Houston, and university collections at Hampton University, Hampton and Texas Southern University, Houston. He passed away in Houston in 2001.