The Man and the Machine: Andy Warhol, Photography and Everyday Life

By Cammie Tipton, Assistant Curator, Public Art UHS

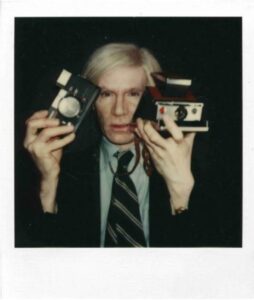

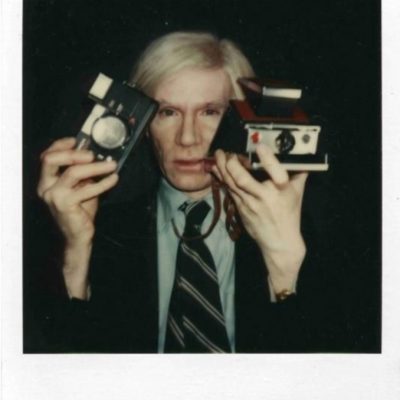

July 2021 | Far from the vapid, partying, destructive persona that Andy Warhol (1928-87) presented, he was more so a hardworking, clever, skilled artist who was always two steps ahead of his own game. Warhol served as a cultural anthropologist to the global Pop era of the 1960s through the 1980s, a time of great American optimism, and he utilized every technology available to obsessively document it. Cameras were central in his daily life and equally a vital component of his artistic process. It was his camera that allowed the shy, self-conscious man access to a rarified crowd of celebrities and socialites while simultaneously enabling him to hide behind the lens. Through the camera, he observed and collected images of the people, social interactions, artworks and ephemera that exemplified a triumphant post-War America.

A true multimedia artist, Warhol was always eager to adopt new technology. The 1970s and 1980s saw the initial transition from analog to digital, and as more technologies were becoming smaller and portable—such as the first handheld video camera, the portable audio recorder and the instant Polaroid—this portability enabled Warhol to capture the brilliant spectacle that was his daily life. In his career, Warhol produced a massive archive of photographic images because, as he once remarked, “A picture means I know where I was every minute. That’s why I take pictures. It’s a visual diary.”

In 2008, Public Art UHS received was gifted 149 carefully curated photographs from the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts through its Photographic Legacy Project, launched in 2007 in celebration of the Foundation’s 20th anniversary. Through this unprecedented program, the Warhol Foundation donated thousands of photographs to university-based museums and galleries across the United States, enabling these institutions to expand scholarship and general interest in Warhol’s more unknown areas of work. The gift to Public Art UHS is comprised of ninety-nine Polaroids and fifty black and white silver gelatin prints that together form an intimate snapshot into the last decade of Warhol’s life from 1975 to 1985.

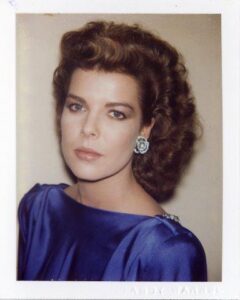

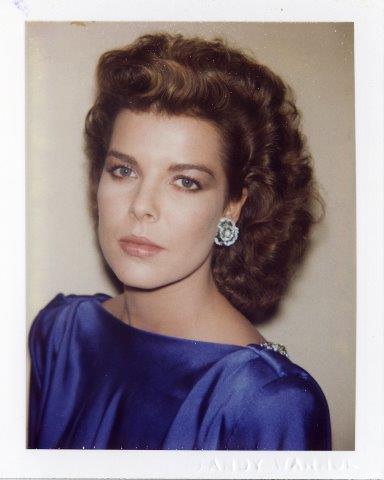

Polaroids were the initial step in executing the portrait commissions that provided Warhol with a steady stream of work and income in the last decades of his life. His silkscreened and painted portraits of wealthy clients were so popular by the 1980s that he held a backlog for months. He would take dozens of quickly snapped Polaroids, which he called his “pen and pencil” and functioned much like traditional sketches. Then he and the client would choose one for the finished product, a full-fledged silkscreened or painted portrait. Each serial image is uncannily like the last, and yet each is an original. The ghostly-powdered starlets and catalog-posed men all appear strangely relaxed in front of Warhol’s camera and the portrait-making process, and the Polaroids, with their harsh flash and unpredictable colors, impart a humanizing effect that makes each sitter appear like an actor in costume. Sitters included the artist and UH alumnus Julian Schnabel, the actress Pia Zadora, and the Dutch model Apollonia Von Ravenstein.

The epic Studio 54 parties, the effervescent Factory, and the cult-of-celebrity were a sort of camouflage that Warhol carefully layered upon himself. In actuality, he was born in Pennsylvania into a lower working class family of Slovakian immigrants. Warhol may perhaps be the first artist to magically transform himself into his own invented “brand.” While Warhol offered a living performance of his own brand, he also actively chose to surround himself with other people who did the same, thus creating a network of celebrities, drag queens, actors, transgender friends, and creators who understood the power of personal transformation. Despite these affectations, simultaneously, Warhol bravely lived as an openly gay man and later withstood the New York City AIDS epidemic.

In contrast, the black and white prints provide a more private view of Warhol, snapshots of moments in his personal life that people rarely got to witness. In his later years he would shoot up to a roll of black and white film per day. The Public Art UHS collection includes several images of his late companion Jon Gould and their quiet life in Montauk, Long Island away from the relentless work and the affected persona that defined his life in New York City. In one image, Gould tenderly carries an infant. In another, Gould and friends enjoy themselves while driving snowmobiles in the mountains.

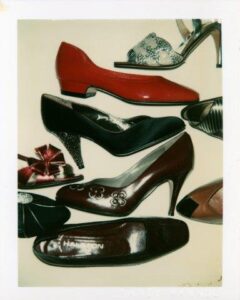

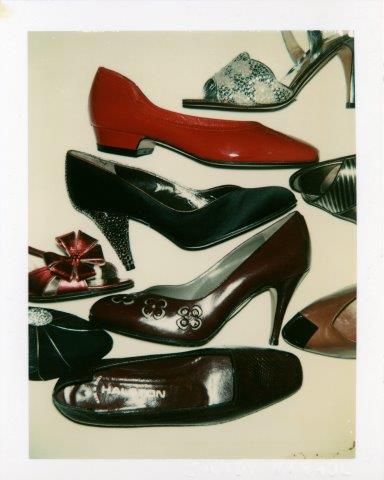

The Public Art UHS collection also includes several unexpected treasures that will delight viewers with a more well-rounded look behind the private persona of Andy Warhol. Such rarities include quiet still lifes of everyday objects including shoes, houseplants and an empty chair; an aerial view from an airplane window, and a native Alaskan ceremonial blanket. Together, the color Polaroids combined with the black and white prints, the photographs bestow a glimpse into the artist’s professional and private life in his final decade.

Through this body of photographic work, Warhol slyly informs us that there is a depth in the void. The banality of the overexposed celebrity and the domestic houseplant afford us a strange satisfaction. He once remarked, “I am a deeply superficial person.” With natural comparisons to Jay Gatsby, Warhol—a self-promoting, entrepreneurial, hardworking, self-made, son of immigrants—is the epitome of the American Dream.

Through this body of photographic work, Warhol slyly informs us that there is a depth in the void. The banality of the overexposed celebrity and the domestic houseplant afford us a strange satisfaction. He once remarked, “I am a deeply superficial person.” With natural comparisons to Jay Gatsby, Warhol—a self-promoting, entrepreneurial, hardworking, self-made, son of immigrants—is the epitome of the American Dream.

All Andy Warhol Artworks © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

A true multimedia artist, Warhol was always eager to adopt new technology. The 1970s and 1980s saw the initial transition from analog to digital, and as more technologies were becoming smaller and portable—such as the first handheld video camera, the portable audio recorder and the instant Polaroid—this portability enabled Warhol to capture the brilliant spectacle that was his daily life. In his career, Warhol produced a massive archive of photographic images because, as he once remarked, “A picture means I know where I was every minute. That’s why I take pictures. It’s a visual diary.”

In 2008, Public Art of the University of Houston System was gifted 149 carefully curated photographs from the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts through its Photographic Legacy Program, launched in 2007 in celebration of the Foundation’s 20th anniversary. Through this unprecedented program, the Warhol Foundation donated over 28,500 photographs to university-based museums and galleries across the United States, enabling these institutions to expand scholarship and general interest in Warhol’s more unknown areas of work. The gift is comprised of 99 Polaroids and 50 black and white silver gelatin prints that together form an intimate snapshot into the last decade of Warhol’s life from 1975 to 1985.

Polaroids were the initial step in executing the portrait commissions that provided Warhol with a steady stream of work and income in the last decades of his life. His silkscreened and painted portraits of wealthy clients were so popular by the 1980s that he held a backlog for months. He would take dozens of quickly snapped Polaroids, which he called his “pen and pencil” and functioned much like traditional sketches. Then he and the client would choose one for the finished product, a full-fledged silkscreened or painted portrait. Each serial image is uncannily like the last, and yet each is an original. The ghostly-powdered starlets and catalog-posed men all appear strangely relaxed in front of Warhol’s camera and the portrait-making process, and the Polaroids, with their harsh flash and unpredictable colors, impart a humanizing effect that makes each sitter appear like an actor in costume. Sitters included the artist and UH alumnus Julian Schnabel, the actress Pia Zadora, and the Dutch model Apollonia Von Ravenstein.

The epic Studio 54 parties, the effervescent Factory, and the cult-of-celebrity were a sort of camouflage that Warhol carefully layered upon himself. In actuality, he was born in Pennsylvania into a lower working class family of Slovakian immigrants. Warhol may perhaps be the first artist to magically transform himself into his own invented “brand.” While Warhol offered a living performance of his own brand, he also actively chose to surround himself with other people who did the same, thus creating a network of celebrities, drag queens, actors, transgender friends, and creators who understood the power of personal transformation. Despite these affectations, simultaneously, Warhol bravely lived as an openly gay man and later withstood the New York City AIDS epidemic.

In contrast, the black and white prints provide a more private view of Warhol, snapshots of moments in his personal life that people rarely got to witness. In his later years he would shoot up to a roll of black and white film per day. The Public Art UHS collection includes several images of his late companion Jon Gould and their quiet life in Montauk, Long Island away from the relentless work and the affected persona that defined his life in New York City. In one image, Gould tenderly carries an infant. In another, Gould and friends enjoy themselves while driving snowmobiles in the mountains.

The Public Art UHS collection also includes several unexpected treasures that will delight viewers with a more well-rounded look behind the private persona of Andy Warhol. Such rarities include quiet still lifes of everyday objects including shoes, houseplants and an empty chair; an aerial view from an airplane window, and a native Alaskan ceremonial blanket. Together, the color Polaroids combined with the black and white prints, the photographs bestow a glimpse into the artist’s professional and private life in his final decade.

Through this body of photographic work, Warhol slyly informs us that there is a depth in the void. The banality of the overexposed celebrity and the domestic houseplant afford us a strange satisfaction. He once remarked, “I am a deeply superficial person.” With natural comparisons to Jay Gatsby, Warhol—a self-promoting, entrepreneurial, hardworking, self-made, son of immigrants—is the epitome of the American Dream.

Public Art UHS’s Warhol photographs are available for viewing by appointment only at the University of Houston Library Special Collections. Learn more about the collection through this feature story by Houston Public Media.

All Andy Warhol Artworks © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.